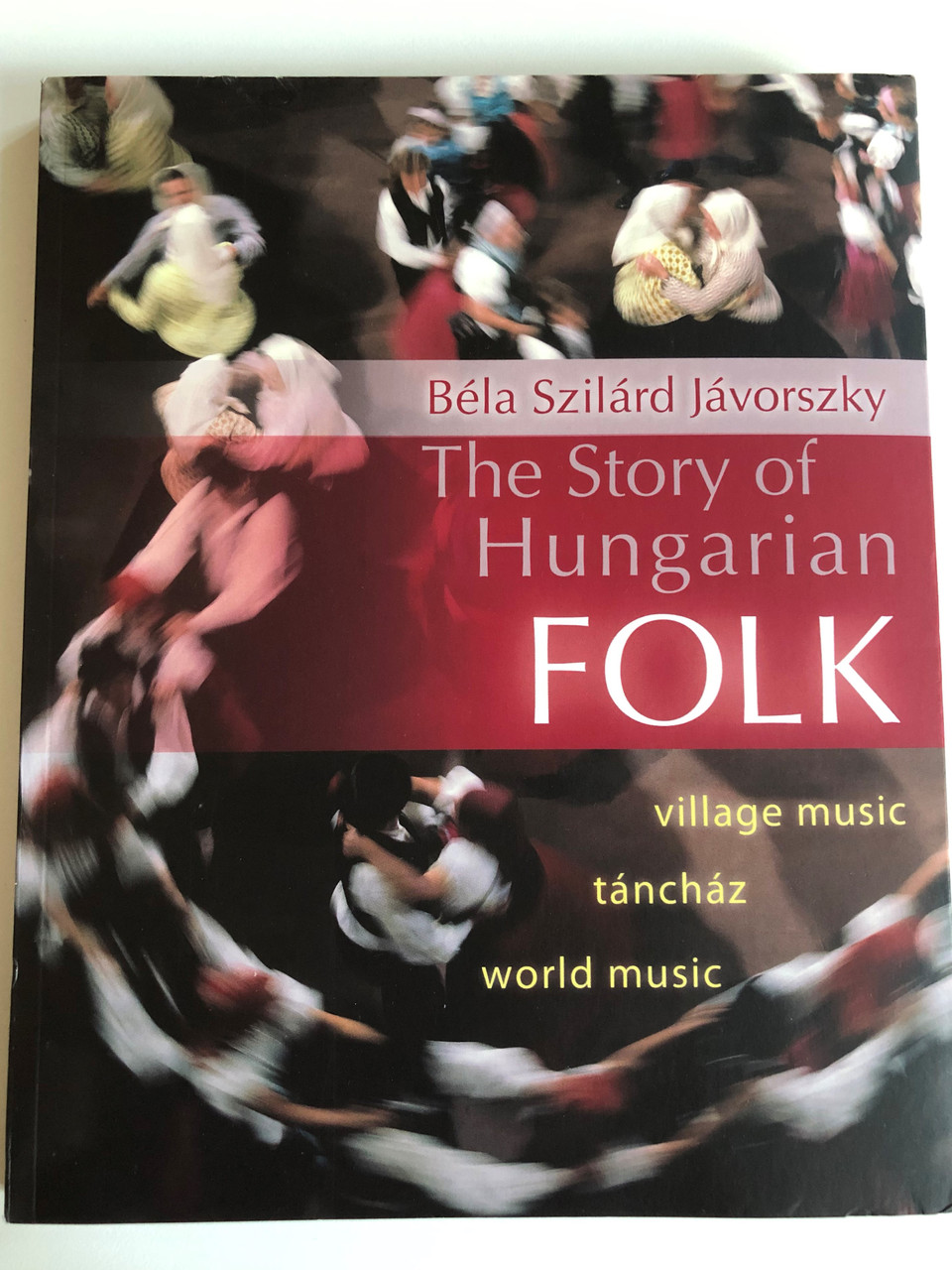

Description

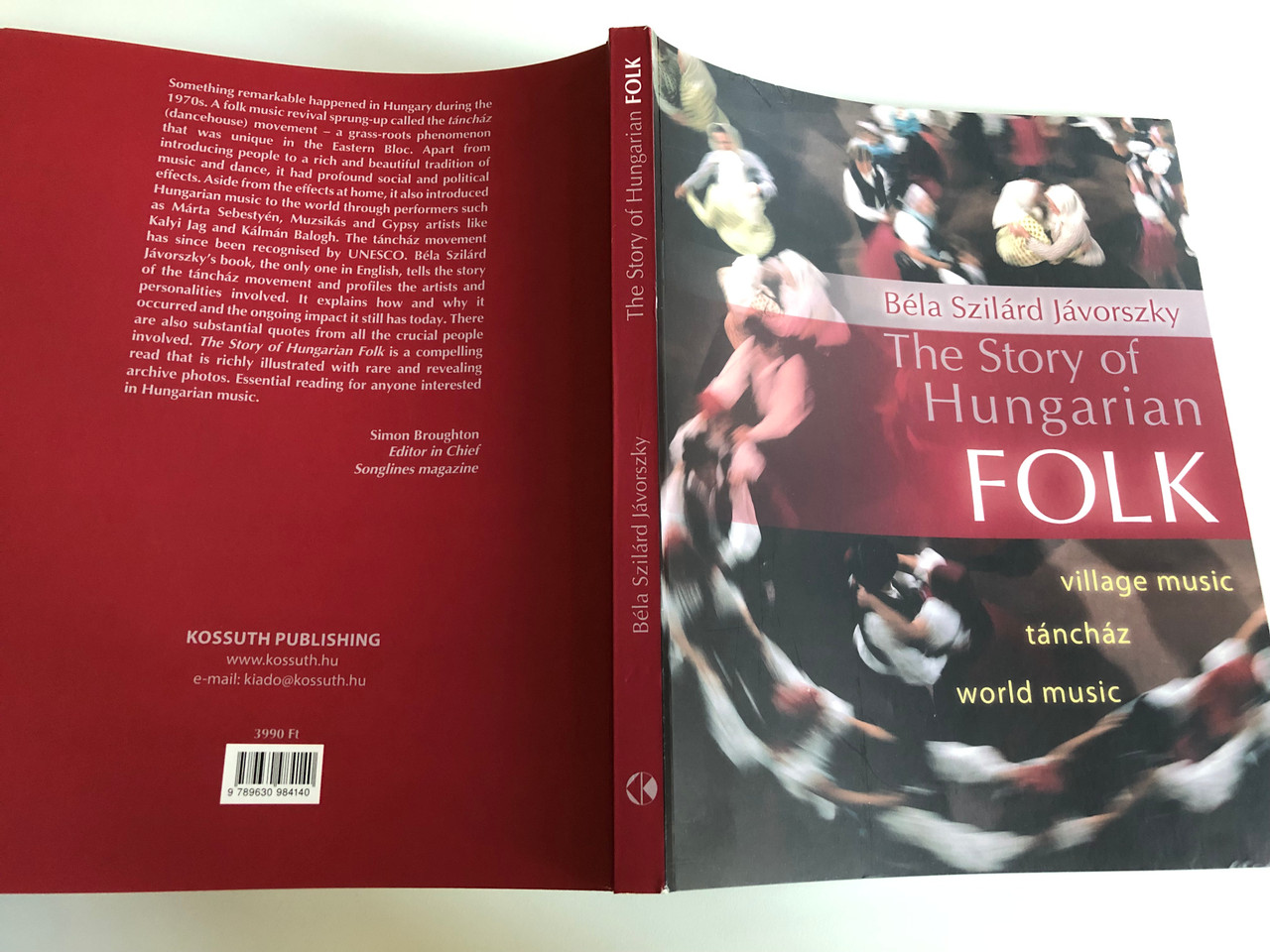

The Story of Hungarian Folk / Author Jávorszky Béla Szilárd / Kossuth Kiadó, 2015

Language: English

Printed in Hungary

Paperback

Publisher / Kiadó: Kossuth Kiadó

Kiadás éve: 2015

ISBN: 9789630984140 / 978-9630984140

Terjedelem: 183 pages

SIZE / Méret: Szélesség: 19.50cm, Magasság: 24.50cm / 460 gramm

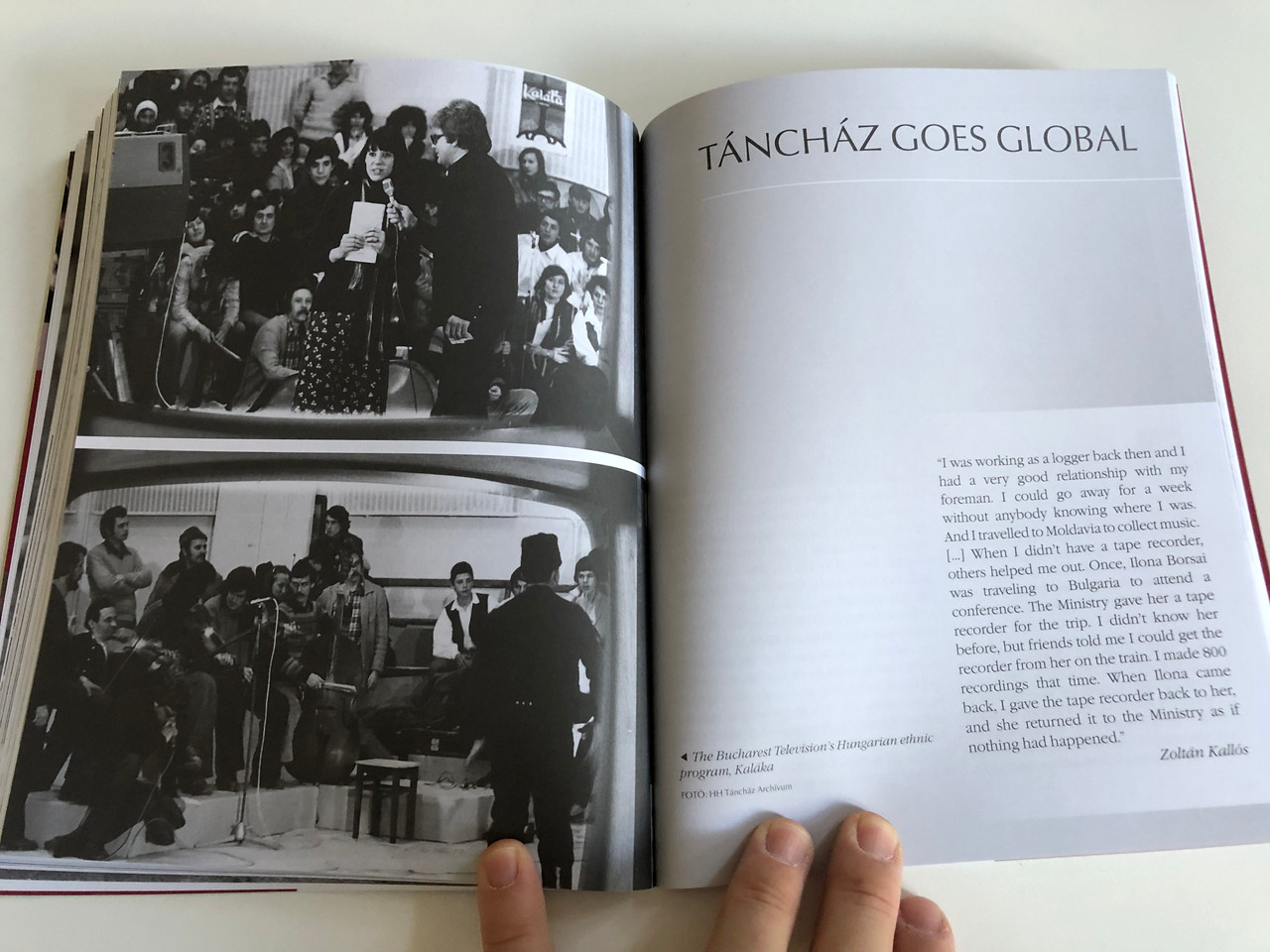

The first táncház in Budapest was held on May 6, 1972. It began as a private event for insiders, but within a year, it was swarming with urban youth. Thus began a grassroots revolution of dance, culture, and lifestyle, organized without political aims, which is referred to today as the táncház movement. And still, the táncház keeps

attracting hundreds of thousands worldwide from Toronto to Tokyo.

The expression táncház literally: dance house comes from Szék (Sic), a small

Hungarian village in Transylvania, referring to their regular dance nights, and an opportunity for having fun, socializing, and dancing. And it soon became apparent that this rural folk tradition could also work in a contemporary urban environment.

This book is the first comprehensive account of the history of Hungarian folk and world music. It is factual, yet easy to read. It sets out to present the social, cultural, and musical ingredients of folk music. It aims to analyse its trends, show the development of different styles, and introduce the key artists and evaluate their contribution to the genre.

(from the Prologue)

Jávorszky Béla Szilárd (Budapest, 1965. július 3.–) zenei szakíró, szerkesztő; a hazai és nemzetközi populáris zene évtizedeit feldolgozó könyvsorozatok szerzője, társszerzője. Fő szakterülete a rock-, a folk-, a jazz- és a kísérleti zene, doktori disszertációját 1991-ben zeneszociológiából írta.

BOOK REVIEW:

A folk revival about so much more than singing songs

In 1970s Budapest, young dancers and musicians defied Soviet dictums; their embrace of traditional village music and dance created the táncház (dance house) movement and provided the foundation for Europe’s most vibrant

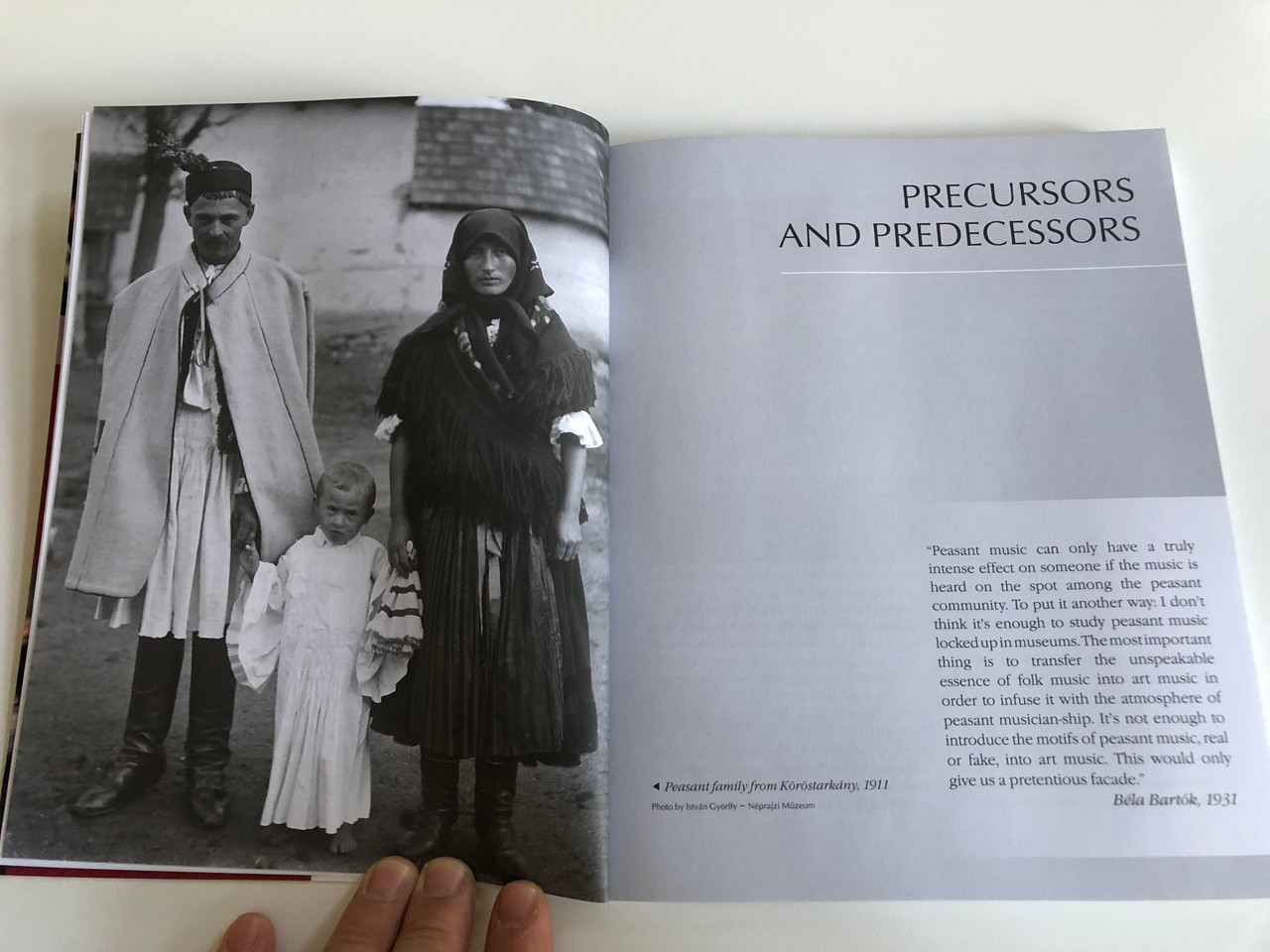

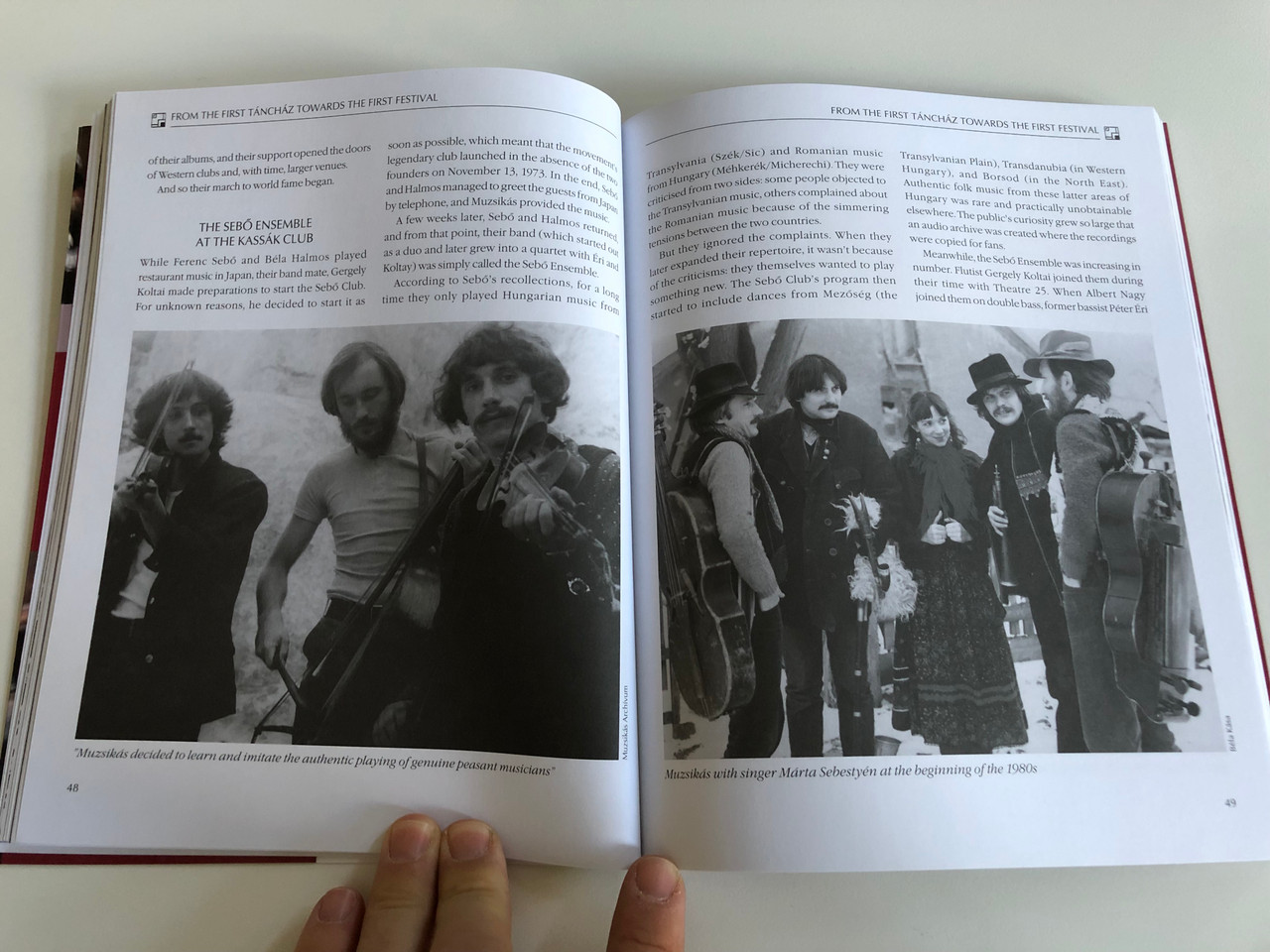

revivalist folk culture. British and American folk revivals pale next to the importance of táncház to the cultural and political history of Hungary. International audiences may well have heard of Márta Sebestyén and Muzsikás but there are dozens of fascinating characters and narratives in the story of táncház; Béla Szilárd Jávorsky tells them all. This book is thorough and easy to read, with plenty of vivid photographs that bring the distinctive look of Hungarian rural culture and its urban emulators to life. Jávorsky shows how the kitsch, overblown approach of Soviet dancing master Igor Moiseyev clashed with the desire of young Hungarians to connect with their own authentic village culture: táncház proved far more fun and sexy than the official choreography.

This book, the only English-language account, is heartily recommended.

My only reservation concerns Jávorsky’s avoidance of controversial issues: while he acknowledges the Eastern bloc

awkwardness of táncház’s cross-border hunt for inspiration in the Hungarian and Gypsy communities of Romanian

Transylvania, he remains quiet about implications of nationalism’s role in fuelling the movement. Is there a connection between táncház’s pride in tradition and the reactionary turn of (folk enthusiast) Viktor Orbán’s ruling

Fidesz party? Many of its policies are hostile to the Roma culture that inspired Hungarian musicians.

This is a well-presented history of a musical movement, its relationships with the composers Bartók and Kodály and its modern offshoots. It shows why táncház has proved such an inspiration to all other folk revivals for its joyful celebration of tradition, its virtuosity, its refusal to separate music from dance and for its generation-spanning longevity. Outside Hungary, it is currently only available through the author (javorszky.bela@gmail.com).

Joe Boyd