Description

Kelemen Quartet - Live at Carnegie Hall / Hunnia Records & Film Production Audio CD 2018 / HRCD 1814

UPC 5999883044179

KELEMEN QUARTET:

Kelemen Barnabás (Violin/Viola)

Varga Oszkár (Violin/Viola)

Kokas Katalin (Violin/Viola)

Kokas Dóra (Cello)

Label: Hunnia Records & Film Production – HRCD 1814

Format: CD

Country: Hungary

Released: 2018

Genre: Classical

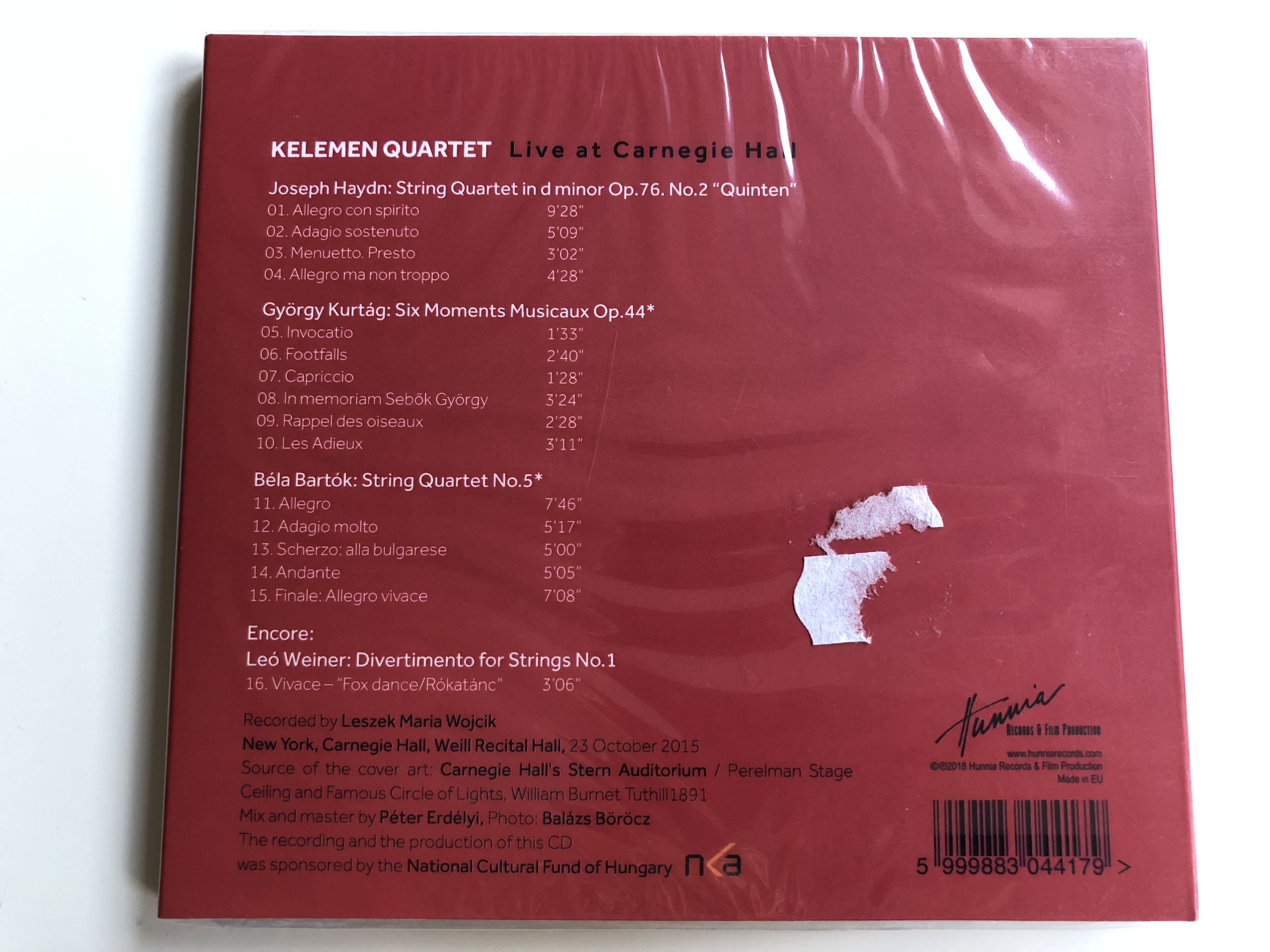

Tracklist:

Joseph Haydn: String Quartet in d minor Op. 76. No. 2 ''Quintet''

01 Allegro con spirito 9:28

02 Adagio sostenuto 5:09

03 Menuetto. Presto 3:02

04 Allegro ma non troppo 4:28

Gyorgy Kurtag: Six Moments Musicaux Op.44

05 Invocatio 1:33

06 Footfalls 2:40

07 Capriccio 1:28

08 In memoriam Sebok Gyorgy 3:24

09 Rappel des oiseaux 2:28

10 Les Adieux 3:11

Bela Bartok: String Quartet No. 5

11 Allegro 7:46

12 Adagio molto 5:17

13 Scherzo: alla bulgarese 5:00

14 Andante 5:05

15 Finale: Allegro vivace 7:08

Encore:

Leo Weiner: Divertimento for Strings No. 1

16 Vivace - ''Fox dance/Rokatanc'' 3:06

- Recorded by - Leszek Maria Wojcik

Kelemen Kvartett: Kelemen Barnabás, Kokas Katalin (hegedű); Homoki Gábor (brácsa); Fenyő László (cselló)

“The most electrifying string-quartet concert in recent memory.” This is the conclusion of an American music critic, otherwise notorious for his fault-finding, concerning the remarkable qualities of the ensemble.

Founded in 2010, the Kelemen Quartet have reaped considerable success in the United States, as well as in Europe and China. The deep commitment of the artists – with Barnabás Kelemen and Katalin Kokas on violin, Gábor Homoki on viola and László Fenyő on cello – is evident in a programme comprising three works that all demand extraordinary levels of concentration. It is widely acknowledged that the string quartets of Béla Bartók are milestones in 20th century classical music. The confessional, sometimes philosophical, sometimes meditative recitatives of the 2nd string quartet strongly resembles the voice of the classic tragedy genre. The structure of the 4th string quartet, built with mathematical precision, represented a kind of creative turning point in the life of the composer and at the same time marked an even more varied and original repertoire of performance technique. In the 6th and final string quartet, a cheery enthusiasm for life and irony descends into a grotesque struggle, with the increasingly feeble, ever-more faint lyricism broken by a motto-like constantly-repeating melody, to ultimately crumble to nothing.

JOSEPH HAYDN String Quartet in D Minor, Op. 76, No. 2, “Fifths”

Haydn was at the peak of his compositional powers when he wrote the six Op. 76 quartets in the mid-1790s. Like his late-blooming masterpiece The Creation, the Op. 76 quartets are notably adventurous in their thematic material, harmony, texture, and timbre. The D-Minor Quartet takes its nickname, and much of its outgoing character, from the boldly striding open fifths played by the first violin at the beginning of the work.

About the Composer

Charles Burney, an industrious chronicler of 18th-century music, lauded Haydn's six Op. 76 quartets as "full of invention, fire, good taste, and new effects." By the time the set was published in 1799, such tributes to Haydn's seemingly inexhaustible creativity were commonplace. After the death of his longtime patron Prince Nikolaus Esterházy in 1790, Haydn took out a new lease on life, spreading his artistic wings and writing in a more extroverted, crowd-pleasing style that reflected the burgeoning public demand for his music. Nonetheless, Haydn was beginning to slow down as he aged. "Every day the world compliments me on the fire of my recent works," he remarked to his publisher, "but no one will believe the strain and effort it costs me to produce them."

About the Work

Composed in the mid-1790s, the Op. 76 quartets betray no sign of flagging energy, much less invention. What Burney described as "good taste" had been a consistent hallmark of Haydn's work from his earliest days. (The title page of the 1799 publication of the quartets depicts the venerable Haydn consorting in the heavens with a pair of angels, one of whom is holding a laurel-wreath halo above his head.) Poised between the Baroque exuberance of Bach and Vivaldi-both of whom were still going strong when Haydn was born in 1732-and the nascent Romanticism of his pupil Beethoven, Haydn's music reflects the Classical virtues of equilibrium, clarity, and seriousness of purpose, tempered with a high-spirited and often earthy sense of humor that has delighted audiences and players for more than two centuries.

A Closer Listen

The D-Minor Quartet takes its nickname from the first violin's boldly striding open fifths (A to D and E to A) in the opening bars. In various forms, this simple two-note motif-sometimes widened to the interval of a sixth or an octave-pervades the entire Allegro: Listen for it in the lower voices as they accompany the brightly lyrical second theme in D major. All four instruments get a piece of the action in the intricate development section, written in Haydn's most engagingly sophisticated conversational style, but the first violin returns to center stage in the limber, lighthearted Andante. Open fifths again feature prominently in the central section of the vigorous Menuetto, andthe quartet ends with a zestful Finale whose skipping, playfully syncopated theme bears a faint but recognizable resemblance to the music in the first movement.

—Harry Haskell

GYÖRGY KURTÁG Six moments musicaux, Op. 44

Kurtág’s compressed and kaleidoscopic sound world marks him as a disciple of Anton Webern, a master of musical aphorism. At the same time, the Hungarian composer has also found inspiration in Bach’s intricately contrapuntal music. From the wary, measured tread of “Footfalls” to the bouncy syncopations of “Capriccio,” Kurtág’s Six moments musicaux cover an astonishing range of sonic and emotional territory.

About the Composer

Hungarian composer György Kurtág once described the compositional process as "continual research" aimed at achieving "a sort of unity with as little material as possible." Like Anton Webern, whose music he came to love long before it was widely known behind the Iron Curtain, Kurtág is essentially a miniaturist. Both his aphoristic musical language and the forces he uses to express it are radically compressed. Yet despite the abundance of "white space" in a typical Kurtág score, his music is densely packed, eventful, and richly allusive. Two threads that run throughout his compositions are a sense of playfulness and a dialogue with friends and fellow composers. This playfulness is reflected in Kurtág's answer to Bartók's Mikrokosmos: an open-ended series of pedagogical piano pieces titled Játékok, or "Games." The dialogue takes the form of numerous musical memorials and homages to composers as diverse as Bach, Schubert, and Stockhausen.

About the Work

Written in installments between 1999 and 2005, Six moments musicaux, Op. 44, is Kurtág's fourth string quartet. Its precursors include the String Quartet, Op. 1; the 12 Microludes, Op. 13; and the Officium breve in memoriam Andreae Szervánsky, Op. 28. As music critic Paul Griffiths has observed, the string quartet "is a medium in which Kurtág is thoroughly at home; he speaks Quartetish as his native language, writing always eloquently with the soft pencil of quartet sounds-a pencil that can be pressed hard to make lines of glistening intensity or barely brushed across the paper, leaving trails like smoke." Indeed, at one stage of his career, Kurtág made a large number of ink drawings in which he literally pressed pen to paper and forced his hand to tremble, generating a kind of spontaneous gestural sketch. His music often seems to spring from a similarly unpredictable impulse. Texture, color, and gesture take precedence over harmony, which Kurtág once described, in characteristically evocative language, as "melody pressed like a flower."

A Closer Listen

Like most of Kurtág's scores, the Six momentsmusicaux are clear and elegant on the printed page-the eye can parse the music as readily as the ear. Here, as in other works, Kurtág reveals himself as an inveterate recycler of his own music; much of the raw material in Six moments musicaux is taken from Játékok. In addition to a number of musical and extramusical allusions (which, fortunately, are not essential to the listener's enjoyment), two of the six movements pay homage to fellow musicians: Hungarian pianist György Sebők and Czech composer Leoš Janáček. Short as they are, the Six moments musicaux cover an astonishing range of sonic and emotional territory, from the wary, measured tread of "Footfalls" to the bouncy syncopations of "Capriccio"; from the slashing, rough-and-tumble energy of "Invocatio" to the chirping harmonics of "… rappel des oiseaux …"; and from the dignified restraint of Kurtág's moving tribute to Sebők to the dirge-like pathos of "Les Adieux."

—Harry Haskell

BÉLA BARTÓK String Quartet No. 5

The fifth of Bartók’s six string quartets was commissioned by his American patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge and had its first performance in Washington, DC, in 1935. Laid out in five movements—three predominantly fast and two slow—the work is notable for its rhythmic verve, richly imaginative tonal effects, and sturdy, arch-like construction.

About the Composer

Bartók was born in Transylvania in 1881 and died in New York City 64 years later. In a manner of speaking, he was exiled twice-first from his homeland and later from his time. Although Bartók's music is rooted in Middle European folk traditions and late-19th-century impressionism, it was forged in the crucible of the early 20th century. Many of his early works are suffused with the melodies, rhythms, and colors of the Hungarian and Balkan peasant music that he collected as a pioneering ethnomusicologist. By contrast, the boldly expressionistic masterpieces of the 1930s and '40s, such as the Violin Concerto and the Concerto for Orchestra, exude the restless, tormented spirit of W. H. Auden's "Age of Anxiety."

About the Work

Bartók's six string quartets, composed between 1908 and 1939, have achieved the canonic status of modern classics. Like Beethoven, the Hungarian composer used the quartet as a vehicle for expressing his deepest and most personal musical thoughts. The quartets chart a course from the impassioned Romanticism of his early period to the bleak pessimism of his later works. As composer-critic Virgil Thomson wrote, "The quartets of Bartók have a sincerity, indeed, and a natural elevation that are well-nigh unique in the history of music."

Composed in 1934 at the instigation of the venturesome American patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, Bartók's Fifth Quartet received its premiere in Washington, DC, the following year on a program with two other uncommonly challenging works: Beethoven's B-flat-Major Quartet, Op. 130, and Berg's Lyric Suite of 1926. Bartók's music has much in common with Beethoven's late-period quartets, not least its intricate contrapuntal texture and searing emotional introspection. Yet Bartók, like Berg, had a deep-seated conservative streak, and for all its angularity and dissonance, the Fifth Quartet is neither particularly obscure nor difficult to listen to.

A Closer Listen

The quartet's five movements are constructed like an arch, with the central Scherzo bridging a pair of somberly spectral slow movements, which in turn rest on two thematically related outer movements of a predominantly urgent and somewhat frenetic character. Perhaps the music's most immediately striking and accessible feature is its rhythmic vitality. Bartók's inventiveness in the rhythmic sphere was matched in the 20th century only by a handful of composers, such as Stravinsky and the great jazz masters. Indeed, the shifting, irregular metrical patterns of the folk-influenced "Bulgarian-style" Scherzo have an almost jazzy swing. Similarly, the overpowering intensity of the first and last movements arises largely from the insistently propulsive rhythms and the characteristically Bartókian repetition of small metric cells that cascade over one another in a relentless torrent of notes.

Other important elements of Bartók's captivating sound-world are the special tonal effects: swooping glissandos, ghostly muted passages, and tinny tremolos played with the wood of the bow touching the string. Bartók's palette of timbres and textures is almost as inexhaustible as his rhythmic invention. Now and then a snatch of diatonic melody breaks through the music's bustling chromatic surface. Just before the end of the quartet, the inner voices break into what sounds like a simple nursery tune. But this half-remembered song of innocence fades quickly, and the music resumes its helter-skelter course toward its unforeseen goal: a startling unison B-flat.

—Harry Haskell