Description

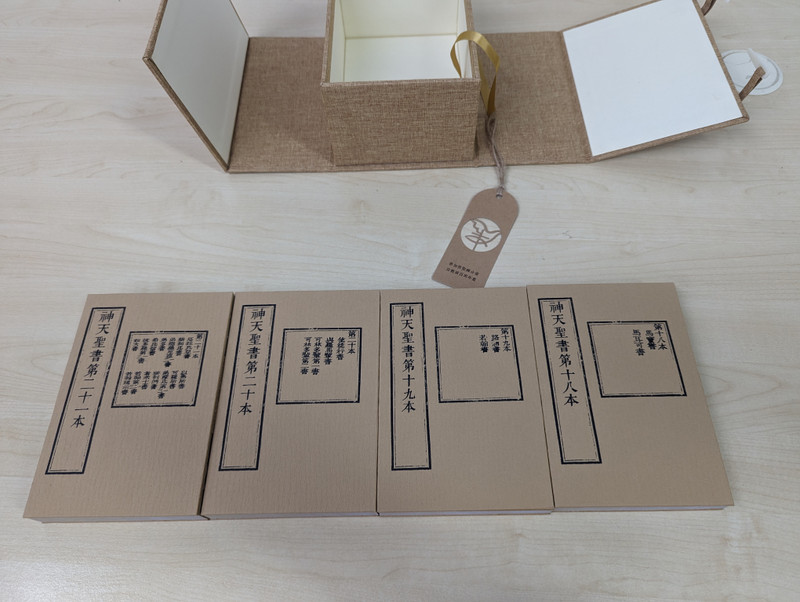

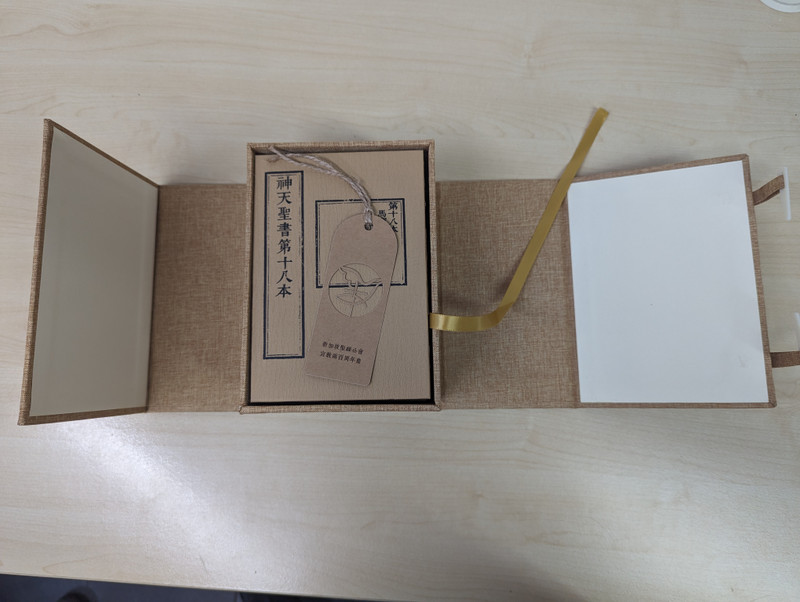

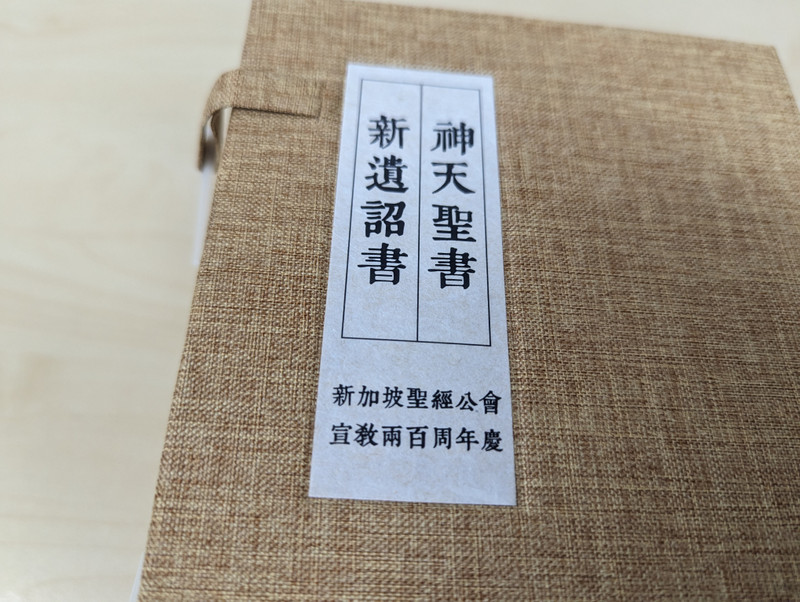

Journey into the Heart of Chinese Protestantism with Morrison's Chinese New Testament 1823 REPRINT Edition

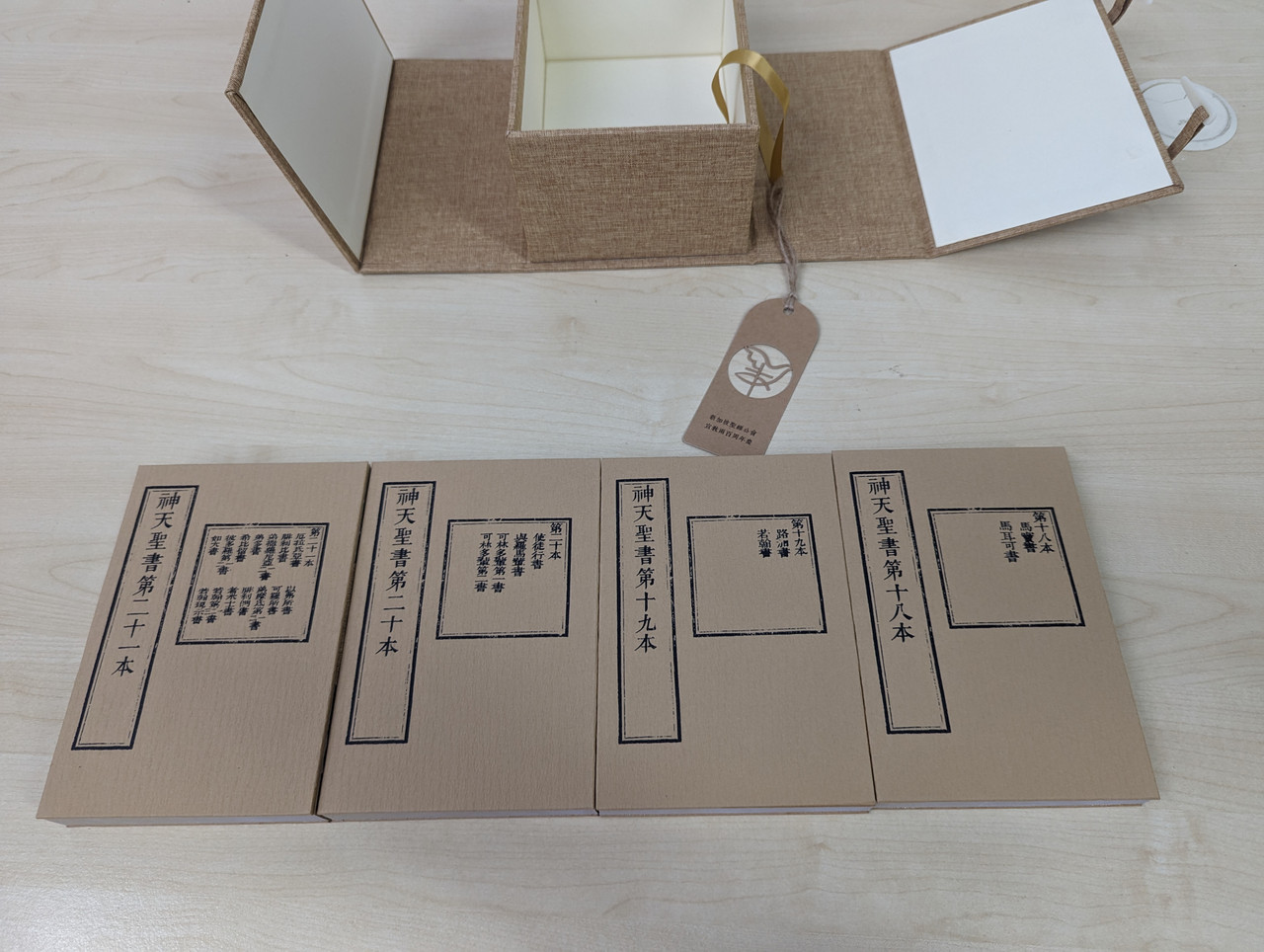

A Rare 4 Volume Set!

Collectable, Rare, A True Relic of History

Product Details:

- Paperback

- Language: Chinese

- Shipping Weight: 5 pounds

Summary:

CHINESE BIBLE TRANSLATION HISTORY:

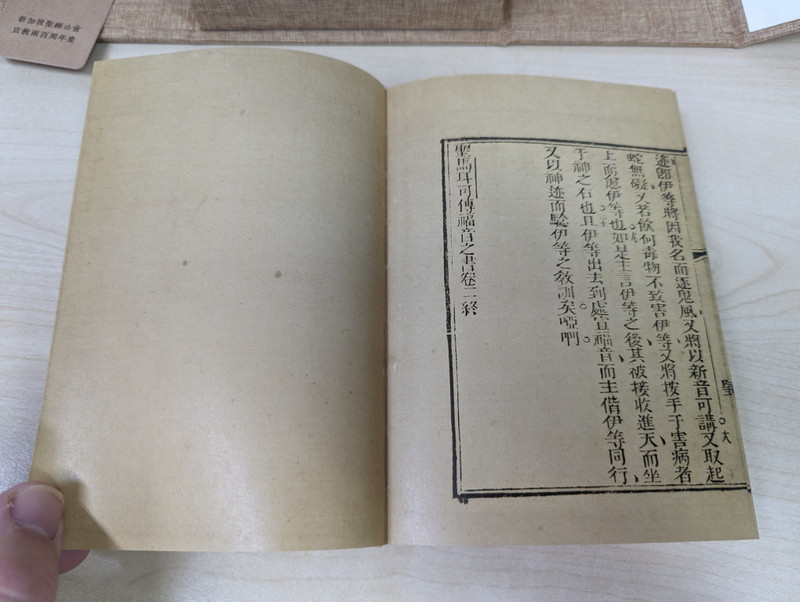

WENLI VERSIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES

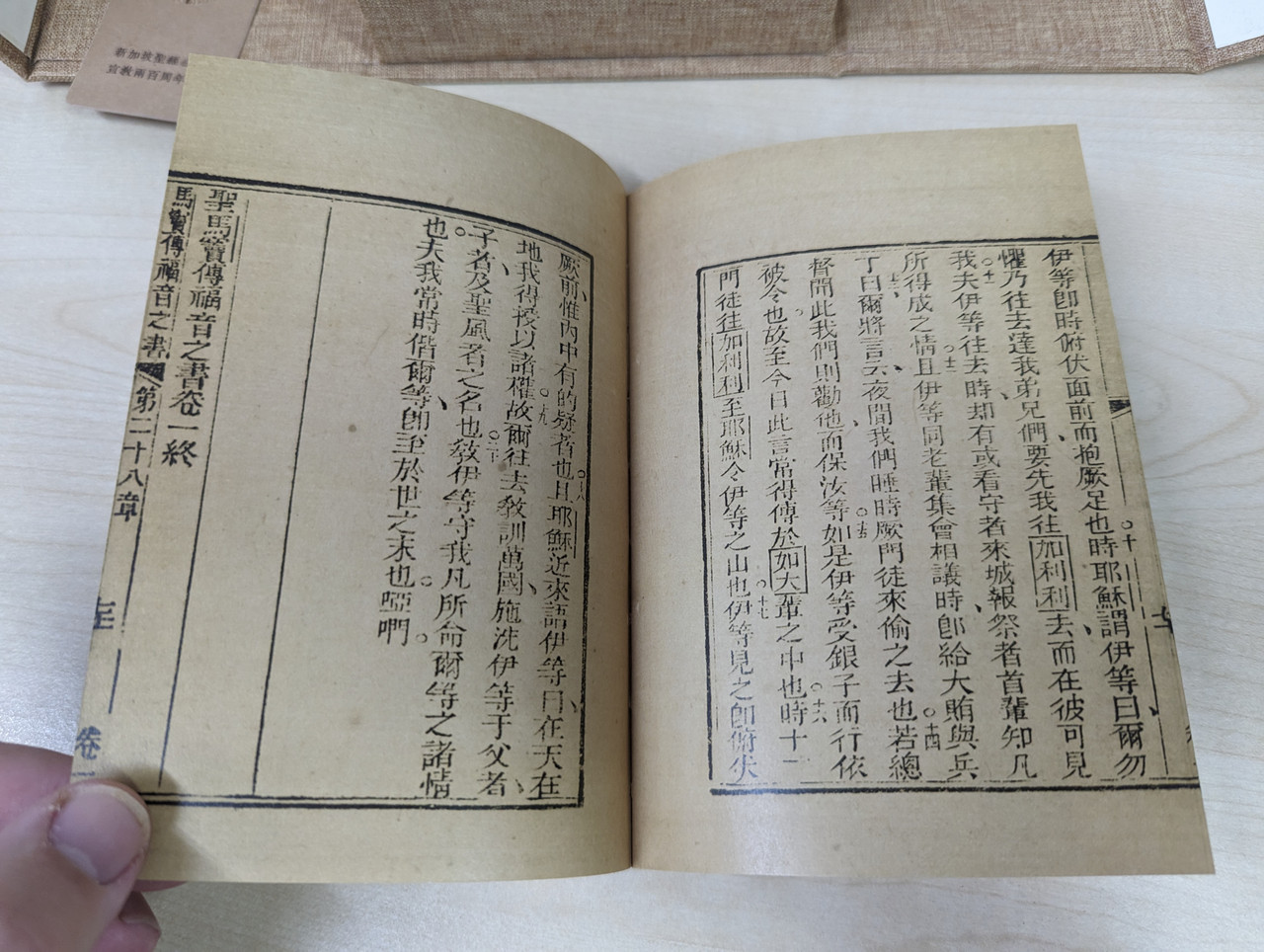

The first translations of the Bible into Chinese were in Wenli, the literary language of China. Chinese ideograms are read differently in each of the Chinese languages and dialects (much as, for example, Arabic numerals are “read” differently in the various European languages); but Wenli functioned as a common idiom for them all. Only a relatively small percentage of the population actually mastered this literary language, however, because to do so requires years of study; nevertheless it was employed by translators for the better part of the 19th century, for the versions of the Scriptures they were preparing were intended primarily for literate Chinese.

The first complete book of the Bible published in Wenli was the Gospel of Matthew, printed in 1810 in Serampore, India. The translation was done by Joshua Marshman, a Baptist missionary from England, assisted by John Lassar, an Armenian born in Macao. Their translation was based on the Greek New Testament and the English King James Version. Matthew was printed from woodblocks, in a very small quantity. A list of Bibles on sale at the British and Foreign Bible Society’s book depot in Calcutta in April, 1810, included this title among those offered for sale. Later in the same year Marshman and Lasser also published a translation of the Gospel of Mark.

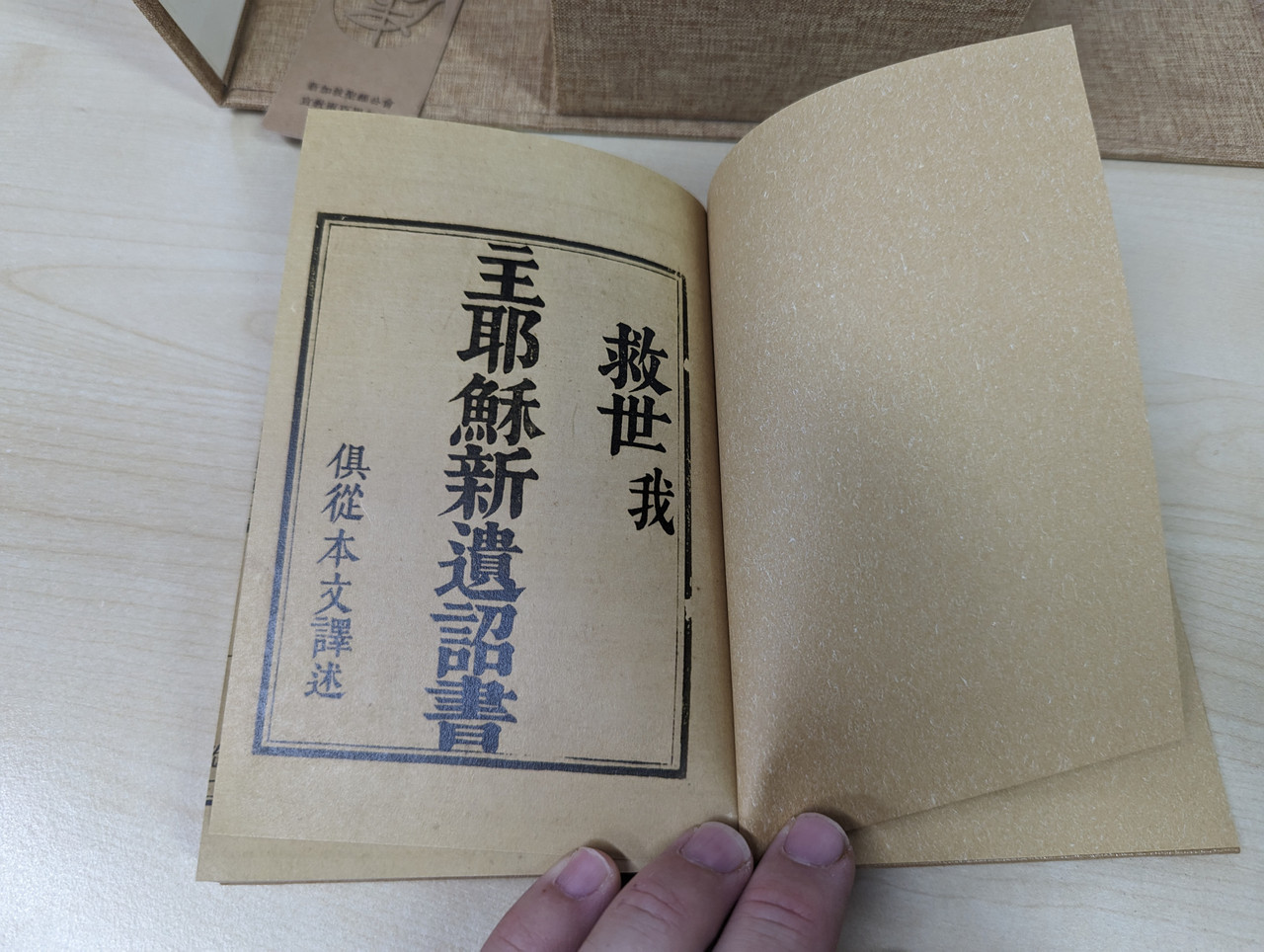

At the same time another translation of the Scriptures was being prepared in the Chinese port city of Canton. The two men responsible for this project were Robert Morrison-to whom reference has already been made-and William Milne. Morrison had come to China in 1807, having been sent there by the London Missionary Society for the specific purpose of translating the Bible into Chinese. A man of keen intellect, he had begun the study of Wenli before he left London, learning the Chinese script from an early 18th century New Testament manuscript in the British Museum (Sloane MS 3599). He made a copy of this manuscript to take with him to China, and in fact incorporated some parts of its translation into his own New Testament.

Morrison’s first published portion, the Book of Acts, also appeared in 1810, only a few weeks after Marshman and Lasser’s Matthew. It was printed from woodblocks, as were all Morrison’s early editions. Copies of this edition of Acts were camouflaged with false covers, in order that there contents would not be easily recognized by the Chinese authorities.

William Milne arrived in China in 1813, and in him Morrison acquired a loyal colleague who could assist in both translation and distribution of the Scriptures. In 1814 Morrison’s New Testament came off the press; and Milne, who had been denied permission to reside in Canton, went to Malacca, Java and Penang to distribute it among overseas Chinese living in these areas.

Meanwhile, Marshman and Lassar in Serampore were making continued progress on their version of the Scriptures. The first complete Old Testament book, Genesis, was printed in 1816 used moveable type, a significant improvement over the laboriously hand-cut woodblocks used previously. The Pentateuch was issued the following year, with other parts of the Old Testaments appearing at intervals over the next five years. These were combined with the New Testament of 1822 to form the earliest published Chinese Bible, each of the five segments bearing on its cover the title of that section, the notice that it was printed with metallic type, and the date.

In fact however, although Marshman and Lassar are credited with publishing the first Chinese Bible, Morrison and Milne had completed their translation three years earlier, in 1819. That it was not published until 1823-almost a year after the version in Serampore-may be attributed to several circumstances, among them the fact that moveable metal type was not available in Malacca, where it was printed, and the translators had to wait for the time-consuming preparation of woodblocks; and also the sudden death of Milne, who had been in charge of the printing, which made it necessary for Morrison to go to Malacca from Macao to oversee the last stages of the work.

Today’s observer of the history of Chinese Scripture translation may well wonder at the fact that two teams of translators covered so nearly identical ground in a time when there was so much else that needed doing. Morrison and Milne apparently knew of the work of Marshman and Lassar, and vice versa; but there was little communication between Macao/Canton and Serampore. The British and Foreign Bible Society was aware of both projects and contributed money to both to assist in meeting publication costs, apparently feeling that in view of the difficulties surrounding the translation of the Bible into Chinese more than one version was desirable. The newly organized American Bible Society also gave some measure of support to Morrison and Milne; and a copy of the first Bible was send to the A.B.S. by Morrison in appreciation of that support.

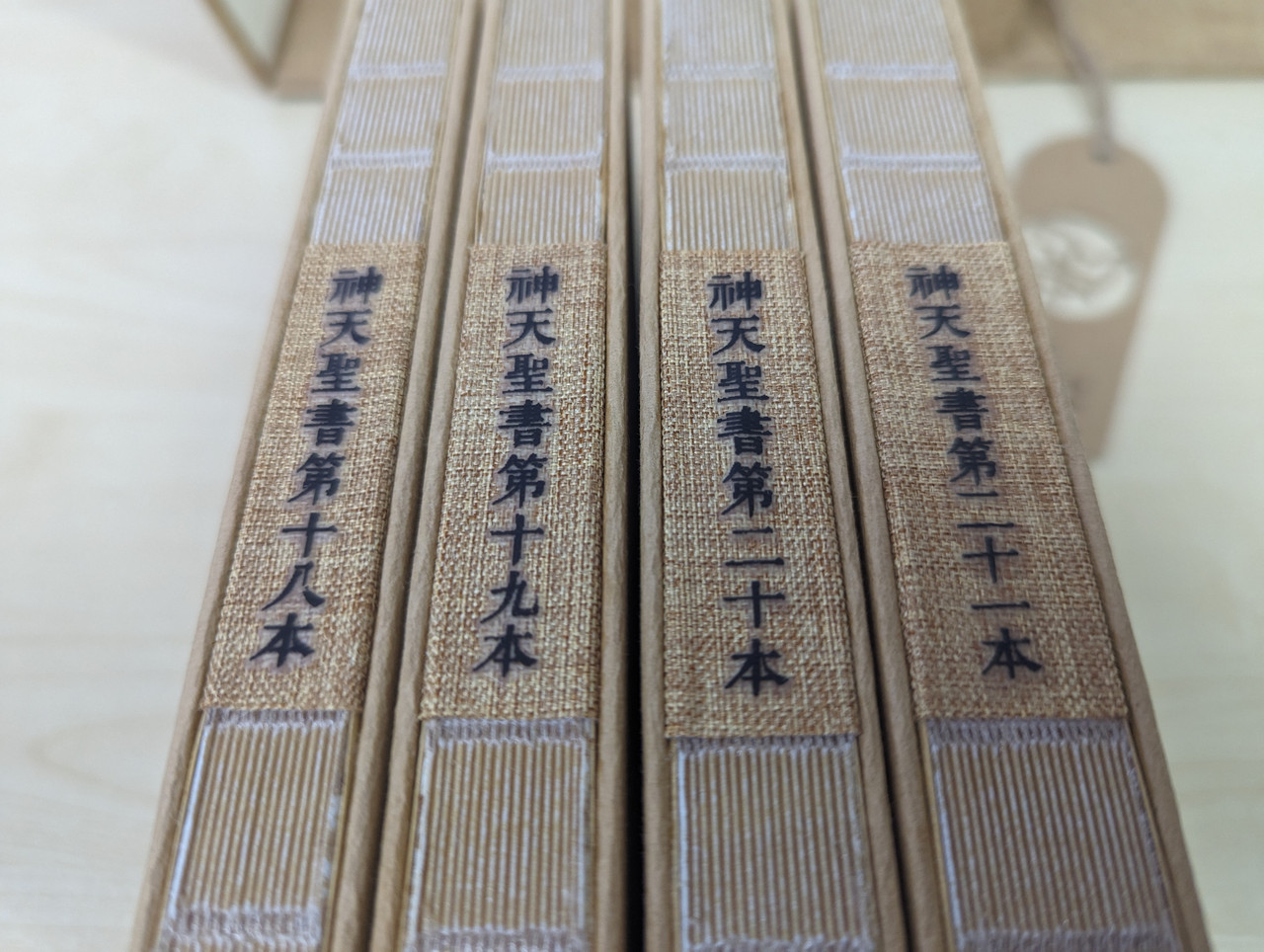

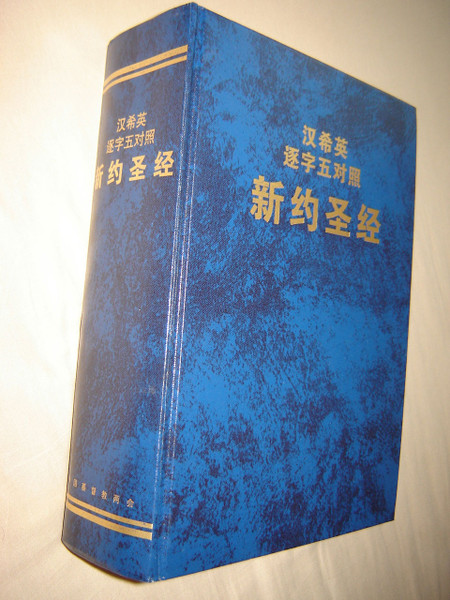

Morrison's Chinese New Testament 1823 REPRINT Edition / 4 volume Chinese Protestant New Testament

![English & Chinese New Testament-PR-FL/RSV (Chinese Edition) [Hardcover] English & Chinese New Testament-PR-FL/RSV (Chinese Edition) [Hardcover]](https://cdn11.bigcommerce.com/s-62bdpkt7pb/images/stencil/600x600/products/602/473/1__08570.1462823109.JPG?c=2)